October Days in Italy with YIVO

YIVO Study Tour to Northern Italy, October 10-22, 2023

by BRIAN AND ONELLA STAGOLL

Days before our study tour met in Milan, Hamas suddenly began a genocidal attack on Jews in Israel. It was the worst violence against Jews since the Holocaust. As our group met, feelings of shock, grief, rage, and despair were surfacing. This became the undertow of the tour—its dark shadow—as we struggled to make sense of what had happened, and what might come next.

For the group the bus became our shtetl, a place we stuck together with emotions otherwise too big to have alone but that might be shared. We reached out for solace and safety together.

We were a mixed group: Americans and Australians, religious and secular, liberal and conservative, all bound by connections to Yiddish and memories of the Holocaust in our lives. Being together gave comfort, but it felt strange to be touring Italy at such a time. Mostly there was dismay and disbelief.

Sam Kassow offered a historical perspective by reading Sholem Aleichem’s great story, Dreyfus in Kasrilevke (1902).

The story begins: “I doubt if the Dreyfus case made such a stir anywhere as it did in Kasrilevke.” Every day the narrator reads from his newspaper newly-arrived at the post office to the gathering crowds in the little shtetl, while the Dreyfus trial proceeds in Paris.

Everybody has an opinion. But when Dreyfus is found guilty a second time nobody can believe it. The crowd proclaims; “It cannot be! Such a verdict is impossible. It must never be!”

It is a poignant refusal by the shtetl to believe in the full evil of the world. But a tremor of awareness is slowly arising.

The bus was our shtetl, the internet our paper. Sholem Aleichem’s story resounded and our awareness sharpened. From “It must not be!” ... to (as the story ends) … “And who was right?”

Some of us had travelled with YIVO to Poland and Ukraine, but Italy felt different to those journeys. In Italy Jews were always “a minority of a minority” (0.1% of the population). This could not compare with Eastern Europe. At first it felt there would be not much to learn. How was it relevant?

But over the 12 days we found this was not so. Not at all, for there were indeed great historical lessons.

Italy had a Jewish history going back 2,000 years to pre-Christian Roman times, and before the destruction of the Temple. There had been a Golden Age for Jews during the Renaissance, and a Silver Age after the Unification of Italy in 1861 – times when Jews were accepted and influential. In Alexander Stille’s words, there were the times of “Benevolence,” of tolerance, integration, and prosperity. Then, sudden and unexpected reversal: “Betrayal,” with persecution in ghettos and antisemitism[1].

If “It must not be,” then it was… all over again.

Synagogues

Our bus ambled from town to town visiting historic synagogues and ghettos: Turin, Asti, Casale Monferrato, Genoa, Florence, Sienna, San Gimignano, Bologna, Modena, Parma, Carpi, Trieste, and finally Venice.

The synagogues were centuries old, often small, and hidden away on top floors not visible from the street. They were full of treasures, with gold and silver gilding, stones and gems, coloured glass, precious woods and fabrics and ornate candelabras and carvings. They were lovingly preserved by their small communities, or what was left of them. They echoed a sad, melancholic beauty, now slowly fading into history.

All the synagogues were guarded by soldiers. You knew you were close to a synagogue when you turned a street corner and met the military.

Only in Venice in the Nuovo Ghetto with its five synagogues did we experience less melancholy. Venice had been the first ghetto, established in 1516 (with the original aim of protecting Jews!).

It had degenerated over the years. The synagogues had slowly collapsed into states of ill-repair, with woodworms, flaking paint, and collapsing plaster. Then four years ago magnificent restoration work began for the German (Scuolo Tedesca, 1528), Canton (1532), and Italian (1570) synagogues. David Landau, leader of the restoration project, gave us privileged access to the ongoing work, and showed us ancient rooms where bent heads were necessary and temperatures were extreme. As Landau put it, “We want visitors to have a sense of what it felt like – it was difficult living. I would like people to know: This is who we are. This is what we have done.” But there was also a modern touch... bulletproof windows on the first floor.

The synagogues were becoming little gems again with the restoration preserving the memory of Jewish life and survival despite all the obstacles.

It was inspiring.

Turin

Primo Levi writes of his ancestors:

“Rejected or given a less than warm welcome in Turin, they settled in various agricultural localities in southern Piedmont, introducing there the technology of making silk, though without ever getting beyond, even in their most flourishing periods, the status of an extremely tiny minority: they were never much loved or much hated: stories of unusual persecutions have not been handed down. Nevertheless, a wall of suspicion, of undefined hostility and mockery, must have kept them substantially separated from the rest of the population even several decades after the emancipation of 1848…” — From The Periodic Table, 1984.

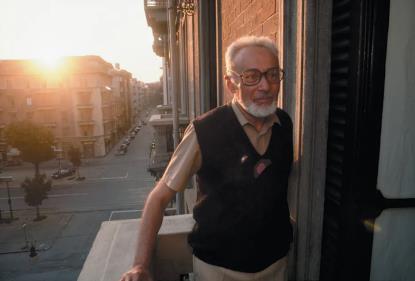

We drove past the apartment where Levi lived all his life apart from his times in Fossoli, Auschwitz, and Russia. He is the firm, clear and gentle voice we need more than ever. In the face of oppression and horror he offers the possibility that humans will not be easily—or completely—abolished.

“We must be listened to: above and beyond our personal experience, we have collectively witnessed a fundamental unexpected event, fundamental precisely because unexpected, not foreseen by anyone. It happened, therefore it can happen again: this is the core of what we have to say. It can happen, and it can happen everywhere.” — From The Drowned and the Saved, 1986.

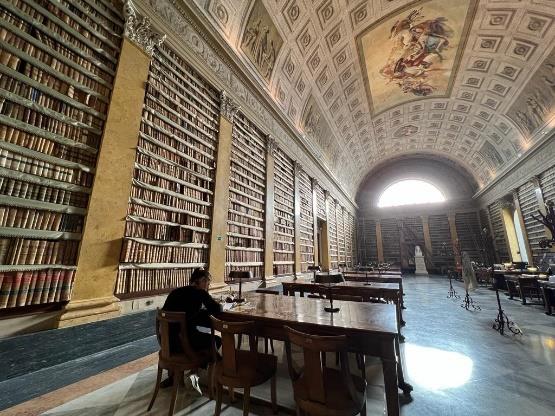

Parma: Biblioteca Palatina

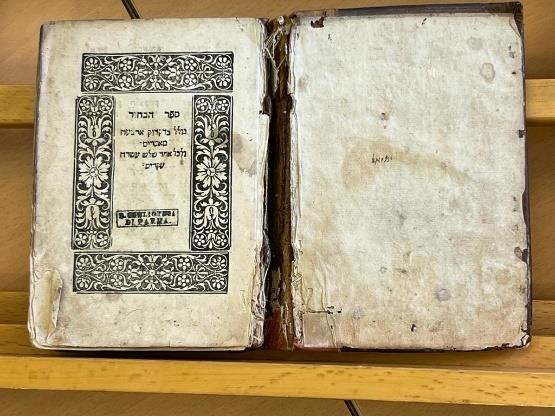

Established in 1761, this magnificent library holds one of the richest collections of ancient books in the world, including one of the largest treasuries of Hebrew manuscripts anywhere.

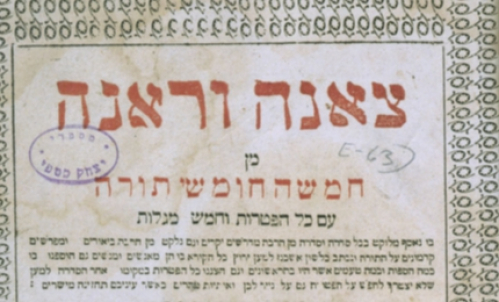

It is estimated that only a very small number of Hebrew manuscripts survived. There was systematic destruction from the Inquisition and Christian persecution aimed at converting Jews. In addition, for ritual reasons many texts—particularly Torah scrolls—were buried as damaged. But if the Catholic Church banished Jewish books, some Catholic Hebraists such as G.B. de Rossi collected and preserved them. Many are in the Palatina.

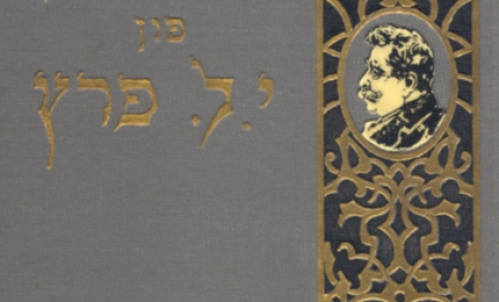

Max Weinreich came from YIVO to locate a small shelf of early Yiddish books. We were shown four of the books by a scholar who discussed their renewal and interpretation with our group. It was an experience that showed that the Palatina was no mausoleum, but a living, organic space, an affirmation that Yiddish scholarship continues beyond West 16th Street, New York.

Nervi and Sholem Aleichem

Nervi, east of Genoa in the Italian Riviera, was where Sholem Aleichem at age 50 stayed in 1908 in a villa on a cliff jutting into the sea. He was seeking a cure for tuberculosis, and subject to a rigorous treatment regime.

He wrote: “The doctors had sternly forbidden three things: talking, reading and writing. Whoever understands what it's like for an alcoholic not to drink, a liar not to talk and a woman not to look in a mirror – that correctly apprehends my situation.”[2] So he kept writing, scribbling secretly on his walks. He returned to Nervi often, seeking recovery, but finally died of TB in New York in 1916.

Florence: David and the Golden Age

At the Accademia Gallery we came upon the David of Michelangelo (1504), our favourite Jewish hero. We were startled by its grandeur and perfection, balance and harmony. This was far beyond the photos and cliches we knew. As Vasari said, “after seeing this no one needs to look at any other sculptures.”

It is the great symbol of strength and youthful beauty, upholding the personal and collective freedoms of the High Renaissance.

This was a time when Jewish culture flourished. According to Cecil Roth, the times were imbued with an open and tolerant spirit led by the Medici patrons, a Golden Age of (allegedly) generous freedom to Jewish scholars participating in the “ferment of intellectual activity.”[3] Hebrew joined Latin and Greek as the third language of learning. Italy’s Jewish population reached its all-time high, 120,000, around 1% of the population. (Today it is around 30,000.)

It was not to last. The Counter Reformation was led by Popes who incarnated persecutory zeal. In 1553, Talmud scrolls were burnt in the Campo de’ Fiori in Rome. An infamous Papal Bull in 1555 pronounced the segregation of all Jews in the Papal States. Under pressure from Rome, the smaller rulers of Northern Italy followed suit. By 1571 Florence had established a ghetto. For generation after generation Jews lived and died in cramped, locked-up quarters. By the mid-18th century Jewish life had reached its lowest point, although in some Northern cities and in Venice this was less so.

But even with the spread of the Enlightenment in Europe, “for the Jews in Italy, which had once ranked as the most welcoming land in all Europe, the old intolerance still held sway.”[4] This did not change until after Unification in 1860.

Bologna: The Kidnapping

The case of Edgardo Mortara exemplified this. Bologna had established a ghetto in 1556. With continuing expulsions there was not much Jewish presence left. Bologna had been famous for Jewish printing houses. They were closed by the Papal State.

In 1851 Edgardo Mortara, the sixth child of a ghetto family, was captured and removed from his family because it was believed he had been baptized. He was forcefully taken to Rome. Protests by his family eventually led to international demands, including from Sir Moses Montefiore, for his return.

Pope Pius IX never relented. Edgardo eventually became a Catholic priest. But the campaigns led by Napoleon III, and Mazzini and Garibaldi, significantly weakened the Vatican state and its secular power as Unification proceeded. A recent Italian movie, Rapito (Kidnapped), directed by Marco Bellochio, tells the story.

We stood in the ghetto near Via dei Giudea and Via dell’Inferno, near where the Mortara house stood (it was demolished in the 1930s). The names say it all.

The Vatican has never apologised. Pope Pius IX was beatified in 2000. Catholic traditionalists still defend the kidnapping.

Ferrara: Giorgio Bassani

The Jewish quarter here is, along with Venice, the largest and best-preserved in Italy. As the capital city of the d’Este Duke, it was a major centre of Judaism in the 16th century, with Ashkenazim from Germany and Sephardim from Spain welcome under local protection. After 1598 and the death of the Duke, the Papacy took control. Jews remained in the ghetto, but later prospered after Unification, often as landowners.

Several prominent families were patriotic supporters of Mussolini. (The opposite was the case in Turin, a centre of Jewish anti-fascist resistance). But the Ferrara allegiance to Mussolini got nothing. 200 Jews were deported to Buchenwald in 1943. Only one returned.

This story is told by Giorgio Bassani, famous for his elegiac, semi-autobiographical novel: The Garden of the Finzi Continis, later made into a film by Vittoria de Sica.

Bassani renders faithful portrayals of Jewish life in Ferrara, a memorial to a lost world with all its conflicts and blindnesses. He never returned to Ferrara, but is buried there.

We walked through the Jewish cemetery, which looked just like the Garden in the movie, with windy gravelly paths, thickets, and many different trees.

Bassani writes: “I suddenly felt myself filled with great sweetness, with peace and tender gratitude. The setting sun, piercing a dark bank of clouds low on the horizon, lit everything vividly. The Jewish cemetery at my feet…”

Trieste: Mussolini

A rich Jewish community lived in Trieste when it was the port city of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, only becoming Italian after World War I. Emancipation from the ghetto came through Emperor Joseph II in 1782. Trieste’s Judaism is linked to Vienna. It was a splendid intellectual and trading city, with fine buildings, coffee houses, and writers (including the famous Jewish writers Italo Svevo and Umberto Saba).

1912 saw the building of the third-largest synagogue in Europe. Trieste was also known as the “Gateway to Zion,” as one of the few ports of embarkation to Palestine.

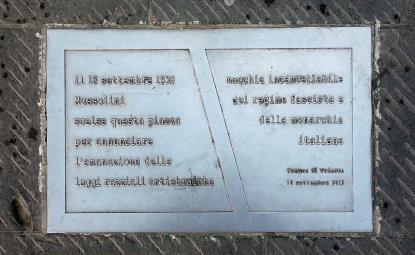

Yet Trieste also had the highest proportion of members of the Fascist party. It was no accident that Mussolini chose Trieste to declare the 1938 Racial Laws in the Piazza Unità d'Italia, the huge square facing the Adriatic. He had given repeated reassurances that he would not institute antisemitic laws. This time he broke all promises, declaring Jews “irreconcilable enemies of Fascism.”

As Umberto Eco puts it: “This body of new law was Italy’s formal endorsement of the Holocaust.”[5]

We stood next to a discreet plaque in the square with Italian and Hebrew inscriptions. It was a chilling moment.

Later we travelled to Risiera di San Saba, a rice-processing factory turned by the Nazis into the only concentration camp in Italy. 5,000 people died here, and many thousands were transported to their deaths. It is now a national monument, preserving the old spaces of imprisonment and death along with moving collections of photos and letters.

Venice: The Lido

It was a relief to get back on the bus to Venice. On our way we played tracks from the album Ghetto Songs, arranged by the famous Klezmer trumpeter Frank London. This had been made to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the ghetto. We sang along to Yiddish songs from Krakow, 17th century Italian music from Solomone Rossi, songs from Cantor Gershon Sirota, and the traditional Ma’oz Tzur. Our hearts lifted.

On our last day in Venice we crossed over the lagoon on Art Deco launches far from the city, to the Jewish cemetery on the Lido. This dates back to 1328 with a tombstone for a certain “Samuel, son of Samson.” It is one of the oldest Jewish cemeteries in Europe, alongside Prague. 1,200 tombstones have been saved and catalogued. Most are bleached, erased or fallen, but symbols and motifs can be made out.

Desolate, disordered, and peaceful, the cemetery was a place to reflect and recall what we had experienced and learnt from our 12 days.

We could have written of much more…on the Padua cemetery and grave of Meir Katzenelonbogen and the Padua museum recreating him on video…the prison camp at Fossoli where Primo Levi was first sent…the National Museum of Italian Judaism and the Shoah in Ferrara, with stunning audio- visuals…the delights of Parmigiano Reggiano and Aceto Balsamico at Giuseppe Guisti in Modena.

But the cemetery was our last place. It was time to go home, tired, but intellectually and emotionally renewed…

Our thanks to Sam Kassow for his generous and deep erudition and talent for filling the gaps in our understanding. To Elissa Bemporad for her scholarship, openness, and sharing her family history, and her guiding us through Modena where she grew up. To Dariusz Kusniar, always affably vigilant, making sure we never got lost or missed the bus. To Ruth Levine and YIVO, and to Irene Pletka, our leader who was unsparing, never missing a beat to ensure we had the best experience possible.

Now back in Melbourne we are anxiously waiting for what might happen next but strengthened by our time with a wonderful group of people. We look forward to our future connections.

[1] Alexander Stille, 1991. Benevolence and Betrayal: Five Italian Jewish Families under Fascism. Summit Books, NY.

[2] J. Dauber, 2013. The Worlds of Sholem Aleichem. Schocken, NY.

[3] Cecil Roth, 1946. History of the Jews in Italy. JPS.

[4] H. Stuart Hughes, 1983. Prisoners of Hope: The Silver Age of the Italian Jews 1924-1974. Harvard.

[5] Umberto Eco, 2020. How to Spot a Fascist. Harvill, London.